Basic Structure of Truckload Market

Learn about carriers, brokers and shippers.

Supply (Truckload Carriers)

The U.S. truckload carrier base is huge (3.68 million Class 8 trucks in operation) — it is also extre mely fragmented.

Though there are several large national carriers with +10,000-truck-fleets, no provider controls enough market share to dictate terms to shippers.

The top ten full truckload-focused carriers only account for around 5% of total truckload market revenue.

In many ways, the hundreds of thousands of owner-operators, small, and medium-sized trucking companies dominate the supply base.

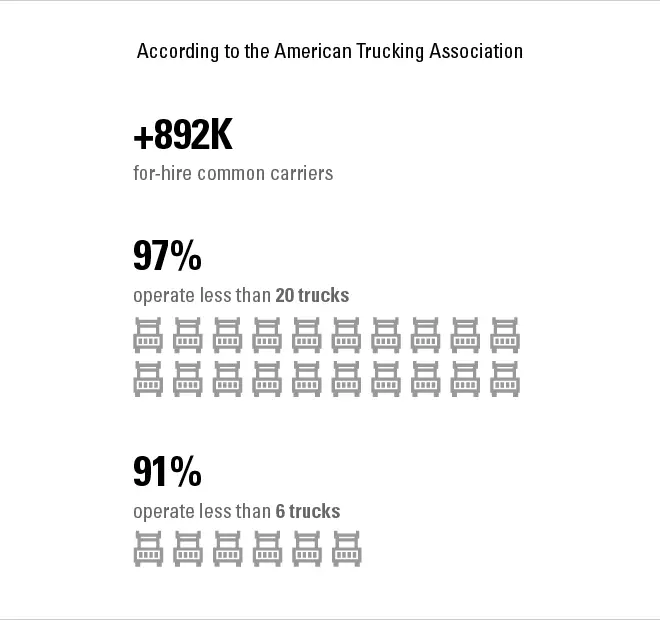

According to the American Trucking Association, there are over 892,000 for-hire common carriers registered with the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. 97% of those companies operate 20 or fewer trucks, and 91% operate less than 6 trucks.

Compare that to the U.S. parcel market, where two carriers (UPS and FedEx) combine for over 75% market share, or the rail industry, where seven Class I railroads control nearly 70% of all rail traffic.

The carrier base, both trucking companies, and individual truck drivers is also very fluid. When times are good, more capacity enters. When times are tough, capacity exits.

Though this dynamic is true in most industries, the rate and frequency it occurs in the truckload market are much faster than other transportation markets. Why? Because the barriers to entry are very low.

It does not take a significant amount of training, time or investment capital to get a commercial driver’s license, lease a truck, and obtain operating authority from the Department of Transportation.

If you wanted to, with a few thousand dollars (and a lot of dedication), you could have your own trucking company in just a few months’ time.

Compare that again to the parcel market: to build a viable consumer option, it would take several massive sorting hubs, dozens of airplanes, thousands of trucks and vans, billions of dollars, and probably a couple of decades.

Or the rail industry, where most of your competitors were founded in the 1800s, are some of the largest real estate holders on the continent and are highly regulated by the federal government.

In short, a huge, fragmented, fluid supply base = market volatility.

Demand (Freight Shippers)

The U.S. shipper base (companies with physical goods to move) encompasses raw materials, finished consumer products, and everything in between.

This means the “demand” half of the equation is no more uniform or consolidated than the supply base.

There are hundreds of thousands of manufacturers, wholesalers, importers, exporters and retailers — each with its own agenda. There are 565,537 Manufacturing businesses in the US as of 2020.

What to ship, how to ship, where to ship and how much to ship, is constantly changing to best meet the demands of each shipper’s customer base.

The barriers to entry (and exit) are also equally low. Any small business that starts shipping products is now in the market.

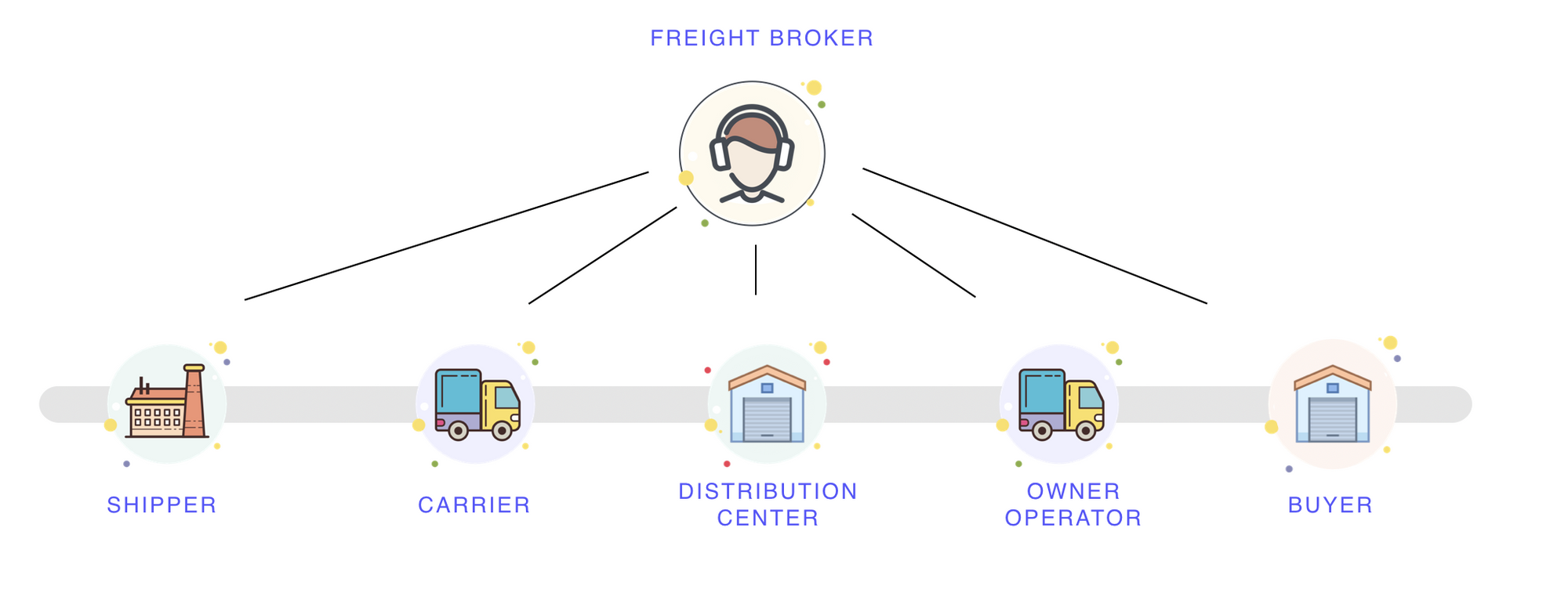

Connecting Supply and Demand (Freight Brokers)

A freight broker is a middleman between shippers and carriers. Instead of taking possession of the freight, the broker facilitates communication between the shipper and the carrier. They’re the ones making sure the handoff goes smoothly between carriers and shippers, and that freight arrives safely, on time.

Shippers like working with freight brokers because they have a single point of contact from point A to point Z while their freight moves to its destination. Working with a broker eliminates the messy process of negotiating with a carrier, planning routes, and tracking freight. Carriers also like working with freight brokers to optimize their routes and minimize deadhead miles, boosting their earnings in less time.

Freight brokers use their expertise to improve delivery times, prevent damage, and increase your supply chain efficiency. These brokers offer lower rates because they combine the freight volume of all the shippers they work with, negotiating lower rates that they pass on to their customers.