3 Cycles of the U.S Truckload Market

Learn how freight markets move up and down

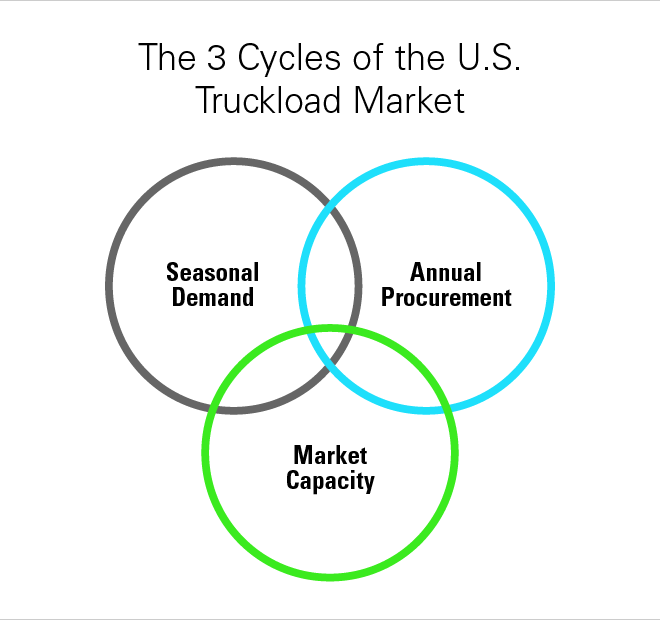

The U.S. Truckload marketU.S. Truckload market is not only massive and fragmented, but also operates under three different cycles at the same time, which adds to the complexity of the market.

While the annual procurement and seasonal demand cycles are easily observed and consistent, the third cycle, the market capacity cycle, is difficult to detect but plays a crucial role in comprehending and effectively navigating the market.

Cycle 1: Seasonal Demand

The initial phase pertains to the variable pockets of seasonal demand that arise periodically and with some degree of regularity.

Several products and commodities do not adhere to a consistent shipping schedule all year round. Instead, they experience a rapid surge in demand over a brief span of time, typically a few weeks or months, in response to pre-planned production or demand windows.

For instance, produce seasons, festive periods, peak retail seasons, Christmas trees during winters, and barbecue items during summers.

Trucks move towards these high-demand areas to make the most of the surge, and after the surge ends, they spread out to other market areas.

The seasonal demand phase is probably the most reliable cycle in the industry. The supply chains are designed to handle the planned demand surges, and trucks serve as a highly mobile production form.

Due to a prepared shipper base and a flexible carrier base, the market usually assimilates these seasonal fluctuations without causing any significant disruptions.

An important consequence of seasonal demand is the occurrence of catastrophic weather events, which have a comparable impact, though unforeseen, resulting in temporary, and occasionally significant, disturbances in both supply and demand.

For instance, recent instances include the 2017 back-to-back hurricanes Harvey and Irma that severely hit the southeastern U.S., leading to record flooding in Houston, Texas, and causing extensive destruction across the area.

The market's effectiveness in absorbing such shocks efficiently relies heavily on the condition of the third cycle.

Cycle 2: Annual Procurement

In general, the freight industry believes that freight rates will increase year after year. Consequently, most shippers with high volumes put out bids for their projected network in order to establish annual "contract" rates.

These rates are intended to provide protection against spot market risks, decrease volatility, and minimize financial risk. Most shippers finalize the bid awards in Q4 and activate them in Q1 of the next year.

Initially, it may appear that an annual procurement cycle would create uniformity throughout the industry.

However, the market's dynamic shifts, which are influenced by three concurrent cycles, along with opposing economic indicators and a tug-of-war for higher and lower rates between both parties, counteract any attempts at stabilization.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of any shipper's procurement strategy hinges on the elusive third cycle, known as the market capacity cycle, which reigns supreme over all.

Cycle 3: Market Capacity

In an inflationary market, shippers often express the following concerns:

- "What is happening in the market?"

- "How much worse will the situation get?"

- "What happened to my freight budget?"

- "How can I become a preferred shipper?"

These apprehensions are prevalent during the inflationary phase of the capacity cycle. The reason behind this is that freight budgets were established during a deflationary period.

Shippers predicted a future rate environment that never came to fruition, and now they are dealing with the repercussions in the form of their freight budgets and service metrics, which are being adversely impacted (both financially and otherwise).

In a deflationary market, carriers frequently express the following concerns:

- "Where have all the loads gone?"

- "Why are spot rates so low?"

- "Will I be able to keep all of my drivers engaged?"

- "How can I become a preferred carrier?"

These worries are widespread during the deflationary stage of the capacity cycle. The reason behind this is that truck orders were placed during a period of inflation.

Carriers projected a future rate environment that never came to fruition, and now their fleet is facing the consequences.

As mentioned earlier, the U.S. truckload market is vast and fragmented, with no single participant able to dictate terms, and entry and exit barriers are low.

This creates fluctuating market pricing that is affected by the ever-changing balance of supply and demand. These two forces are seldom in equilibrium, and even when they are, it is only for a brief period.

When the market becomes attractive to carriers, existing companies will order more trucks while new carriers will seek to enter the market. However, this process is not instantaneous, and it usually takes several months or quarters due to truck build cycles, order backlogs, driver recruitment and training, etc.

At some point in the future, this added capacity enters the market, but the conditions that originally prompted carriers to make these business decisions often change. Carriers may end up overshooting and adding excess capacity, which results in supply exceeding demand.

In other words, carriers buy high, but they have to sell low. Tender acceptance rates increase while rates decline. Shippers take advantage of this and push rates as low as possible to cut costs after experiencing several years of blown budgets.

As rates begin to bottom out, carriers remove capacity from the market, setting up the next inflationary cycle, and thus the cycle repeats.